An eyewitness account of the events in South-America

Published in: EU Observer

Bolivia has dominated international headlines over recent weeks due to disputed election results and protests. Now Pundits divide on the question of whether it was a coup d’état against President Evo Morales or against the Bolivian people.

Many observers have focused on the role the army played in the last hours before Morales resigned. But they have tended to overlook the main player in the three weeks that led to the conflict’s pinnacle: Bolivia’s youth.

A historic election

Regardless of political preferences, the elections on 20 October 2019 were a critical event for the country’s future. At around 8 pm that evening, the rapid vote count was stopped, an act that immediately set off alarms in people’s heads. I thought that the webpage showing the results had crashed due to the scale of interest. The majority of Bolivians thought something else: fraud.

Many were reminded of the 2016 Referendum. After a majority of the population voted against a constitutional change to allow for the indefinite re-election for president and vice-president, this result was later overturned by Morales. He had gotten the Bolivian Constitutional Court to rule that it was his human right to run as many times as he wanted.

Similarly, on the night of 20 October, Morales declared himself the winner. The next day, the rapid counting restarted, giving him enough margin to avoid a run-off and increasing suspicion. Protests started right away.

The surprise factor: youth

The demonstrations following this general election were led by a generation who has known no other president than Evo Morales. Many voted for the first time this year. Some had voted for his party, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), before and were disappointed.

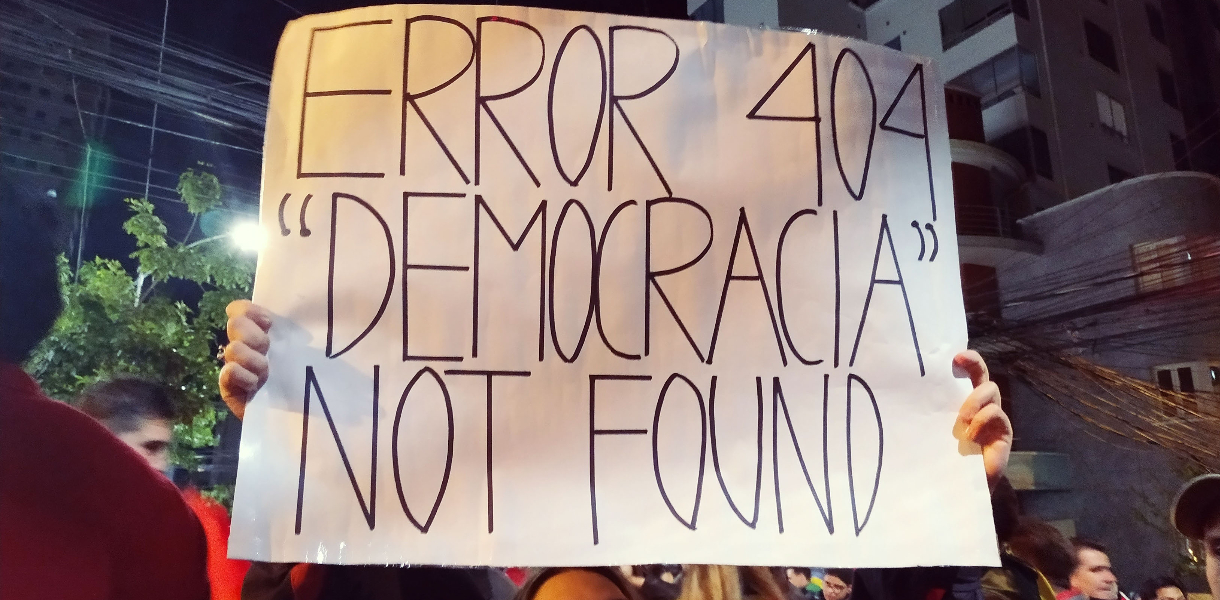

These young people took to the streets with one goal: to defend democracy and the right to free and fair elections.

These young people took to the streets with one goal: to defend democracy and the right to free and fair elections. There was an overarching understanding that without protest, elections in Bolivia would become a farce. Voters would be no more than extras in a show.

The determination of these mainly middle-class young Bolivians was contagious. People of all walks of life and ages joined the street blockades and marches. Emigrés abroad organized rallies to support their actions.

The Venezuela effect

Looming over everything was a feeling that Bolivia could be following the path of another country in the region. “No, no, no. I don’t want to live in a dictatorship like in Venezuela”, was a popular chant on Bolivian streets.

The fear here was not about the economy, which in 2019 was expected to grow 3,8%. The fear was of a different kind. It was about the idea of living in a state depleted of the rule of law, without separation of powers, and where the judiciary is not independent.

On the morning of 10 November, the Organization of American States (OAS) presented the preliminary conclusions of its audit of the elections. It had found various irregularities and recommended a new electoral process.

Later that same day Morales resigned. And even then, young people from my neighborhood were sceptical. They remembered Hugo Chávez in 2002. He was removed from power, but he returned 48 hours later with military backing. Now, almost two weeks after Morales left to Mexico, and following a number of contradictory interviews he gave to the media, the fear of his possible return remains.

Keep the youth involved

Bolivia’s youth was relentless in the days before the president resigned, active day and night, barely sleeping. Morales, and frankly, everybody, in Bolivia, had completely underestimated this generation. At times clumsy, these young people learned on the go. What helped them were unique Bolivian skills: improvisation and solidarity. Most importantly, they insisted on staying peaceful in their protests. And, of course, they used a number of different apps to connect and inform each other. WhatsApp was the main one, but also Telegram, Signal and walkie-talkie apps were in high demand.

The task now is to make sure that these voices are heard.

Before the October elections, most Bolivians would have described the country’s youth as apolitical. That view has changed drastically. The task now is to make sure that these voices are heard. As the main drivers of this historic moment, they should be encouraged to stay active in their communities, civil society and in politics.

Like many recent protest movements, these young people preferred to stay leaderless. Or, alternatively, they would say that they were “all leaders” and that no one was more important than the other. This clearly worked well internally and led them to the finish line.

But past experiences, such as Egypt in 2011, teach us that in the long run, this works to the protesters’ detriment once the time for dialogue comes. It means that no one represents this group’s interests at the negotiation table. This is problematic and potentially a lost opportunity.

Bolivia remains a young country, with half of it being under the age of 25 (census 2012). Irrespective of political color, these young people have the right to be represented. From conversations with them, I know that their understanding of a leader is of someone who imposes, rather than someone who listens and represents. This might explain their aversion of getting involved in politics and to politicians in general.

Europe can both support and learn from them

According to the EEAS website, Bolivia is the main recipient of bilateral aid from the EU for development in Latin America. The Budget for 2014-2020 is €281 million.

The EEAS already works with many civil society groups through its delegation, but can only fund registered organizations. Many of these have a long trajectory and a track record of achievements. But they also stem from a different era, way before our digital and globalized times. Too big to react quickly to new developments and with too much internal red tape, their flexibility is limited.

Morales, like many other authoritarian rulers, made sure to pass a law (in 2013) to restrict civil society. This legislation makes it very difficult to register a new NGO or a foundation and to get funding without the government’s approval. Any new administration should reverse this. But until then, new groups that emerged from the recent protests will find it difficult to access funding and training.

The EU is in a unique position to empower these voices.

It is here that the EU is in a unique position to empower these voices. It can encourage and enable those leading the historic moment to stay active. Not only does the EU enjoy credibility in the region, but it also has at its disposal innovative tools to provide flexible democracy support. The European Endowment for Democracy (EED) – set up by the EU after the Arab Spring – is just such a tool. It has the distinctive ability to grant funding at varying levels to non-registered groups and even individuals. Grants start from as little as 1,000 EUR.

Now in its sixth year, EED has an impressive track record. It has steadily expanded its mandate to new regions of the world, such as Turkey and the Western Balkans. Extending the EED’s mandate to Latin America should be the next step. It would provide funding for new, emerging civil society groups in places like e.g. Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. More importantly, it would provide them with much-needed peer learning opportunities.

What happened in Bolivia is already influencing and rekindling protests in other parts, like in Nicaragua and Venezuela. And as I write this, protests have also started in Colombia. Young Bolivians followed closely events in places as far as Hong Kong and Lebanon. Similar to the youth protests in those countries, the Bolivian protest was a moral revolution. It was fueled by the cynicism of a government that had lost all ethics and respect for its voters.

In return for its support to the emerging civil society in the region, the EU will learn from them what matters to these young societies today. Just like with the Arab Spring, the current events in Latin America took the EU by surprise. It is time to start an honest dialogue with this region. And what better than talking to the new generation.

Gabriela Keseberg Dávalos is a Bolivian-German journalist and political scientist. She was Senior Foreign Policy Advisor to the Vice-president for Human Rights and Democracy of the European Parliament (2013-2016) and now lives in Bolivia.